Archive for the ‘Azure’ Category

Comparison of Cloud Storage Services

When designing workloads in the cloud, it is rare to have a workload without persistent storage, for storing and retrieving data.

In this blog post, we will review the most common cloud storage services and the different use cases for choosing specific cloud storage.

Object storage

Object storage is perhaps the most commonly used cloud-native storage service.

It is been used by various use cases from simple storage or archiving of logs or snapshots to more sophisticated use cases such as storage for data lakes or AI/ML workloads.

Object storage is used by many cloud-native applications from Kubernetes-based workloads using CSI driver (such as Amazon EKS, Azure AKS, and Google GKE), and for Serverless / Function-as-a-Service (such as AWS Lambda, and Azure Functions).

As a cloud-native service, the access to object storage is done via Rest API, HTTP, or HTTPS.

Unstructured data is stored inside object storage services as objects, in a flat hierarchy, where most cloud providers call it buckets.

Data is automatically synched between availability zones in the same region (unless we choose otherwise), and if needed, buckets can be synched between regions (using cross-region replication capability).

To support different data access patterns, each of the hyperscale cloud providers, offers its customers different storage classes (or storage tiers), from real-time, near real-time, to archive storage, and a capability for configuring rules for moving data between storage classes (also known as lifecycle policies).

As of 2023, all hyperscale cloud providers enforce data encryption at rest in all newly created buckets.

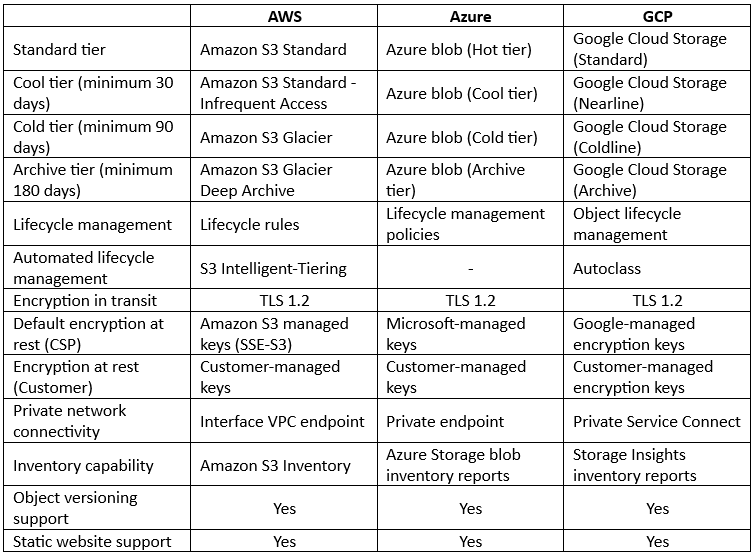

Comparison between Object storage alternatives:

As you can read in the comparison table above, most features are available in all hyper-scale cloud providers, but there are still some differences between the cloud providers:

- AWS – Offers a cheap storage tier called S3 One Zone-IA for scenarios where data access patterns are less frequent, and data availability and resiliency are not highly critical, such as secondary backups. AWS also offers a tier called S3 Express One Zone for single-digit millisecond data access requirements, with low data availability or resiliency, such as AI/ML training, Amazon Athena analytics, and more.

- Azure – Most storage services in Azure (Blob, files, queues, pages, and tables), require the creation of an Azure storage account – a unique namespace for Azure storage data objects, accessible over HTTP/HTTPS. Azure also offers a Premium block blob for high-performance workloads, such as AI/ML, IoT, etc.

- GCP – Cloud storage in Google, is not limited to a single region but can be provisioned and synched automatically to dual-regions and even multi-regions.

Block storage

Block storage is the disk volume attached to various compute services – from VMs, managed databases, Kubernetes worker notes, and mounted inside containers.

Block storage can be used as the storage for transactional databases, data warehousing, and workloads with high volumes of read and write.

Block storage is not just limited to traditional workloads deployed on top of virtual machines, they can be mounted as persistent volumes for container-based workloads (such as Amazon ECS), and for Kubernetes-based workloads using CSI driver (such as Amazon EKS, Azure AKS, and Google GKE).

Block storage volumes are usually limited to a single availability zone within the same region and should be mounted to a VM in the same AZ.

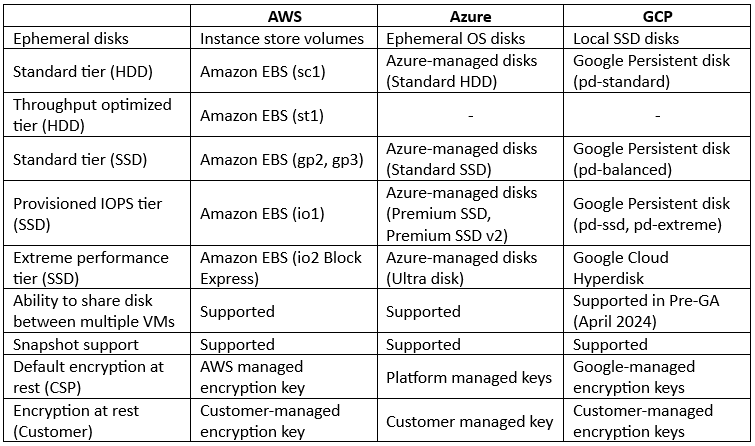

Comparison between Block storage alternatives:

As you can read in the comparison table above, most features are available in all hyper-scale cloud providers, but there are still some differences between the cloud providers:

- AWS – Offers a feature called Amazon Data Lifecycle Manager, which automates the process of creation, retention, and deletion of EBS snapshots.

- Azure – Offers the ability to manage data replication of persistent disks within the same region (Locally redundant storage / LRS and Zone-redundant storage / ZRS) and between primary and secondary regions (Geo-redundant storage / GRS, Geo-zone-redundant storage / GZRS, and Read-access geo-redundant storage / RA-GRS).

- GCP – Offers the ability to replicate persistent disks across two zones in the same region (Regional Persistent Disk). GCP also offers the ability to pre-purchase capacity, throughput, and IOPS to be provisioned as needed (Hyperdisk Storage Pools).

File storage

File storage services are the equivalent of the traditional Storage Area Network (SAN).

All major hyperscale cloud providers offer managed file storage services, allowing customers to share files between multiple Windows (CIFS/SMB), and Linux (NFS) virtual machines.

File storage is not just limited to traditional workloads sharing files between multiple virtual machines, they can be mounted as persistent volumes for container-based workloads (such as Amazon ECS, Azure Container Apps, and Google Cloud Run), Kubernetes-based workloads using CSI driver (such as Amazon EKS, Azure AKS, and Google GKE), and for Serverless / Function-as-a-Service (such as AWS Lambda, and Azure Functions).

Other than the NFS or CIFS/SMB file storage services, major cloud providers also offer a managed NetApp files system (for customers who wish to have the benefits of NetApp storage) and managed Lustre file system (for HPC workloads or workloads that require extreme high-performance throughput).

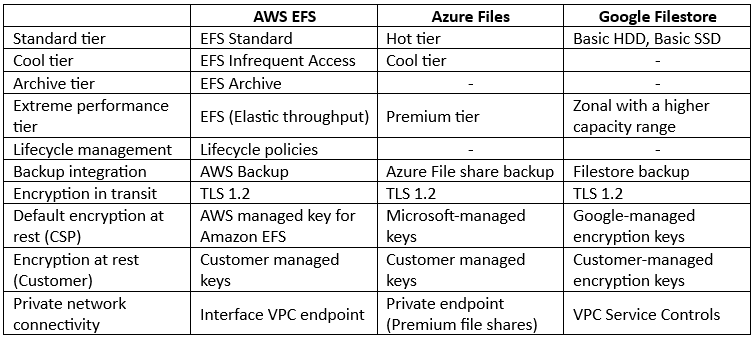

Comparison between NFS File storage alternatives:

As you can read in the comparison table above, most features are available in all hyper-scale cloud providers, but there are still some differences between the cloud providers:

- AWS – Offers cheap storage tier called EFS One Zone file system, for scenarios where data access pattern is less frequent, and data availability and resiliency are not highly critical. By default, data inside the One Zone file system is automatically backed up using AWS Backup.

- Azure – Offers an additional security protection mechanism such as malware scanning and sensitive data threat detection, as part of a service called Microsoft Defender for Storage.

- GCP – Offers enterprise-grade tier for critical applications such as SAP or GKE workloads, with regional high-availability and data replication called Enterprise tier.

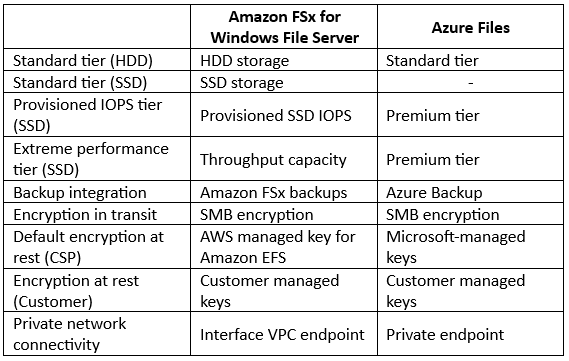

Comparison between CIFS/SMB File storage alternatives:

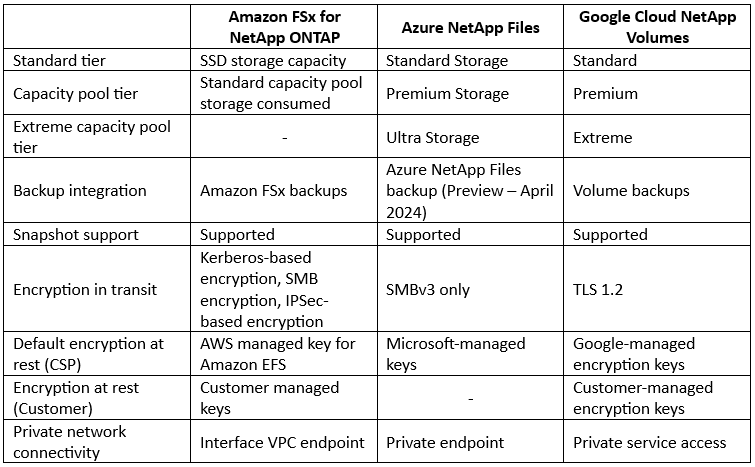

Comparison between managed NetApp File storage alternatives:

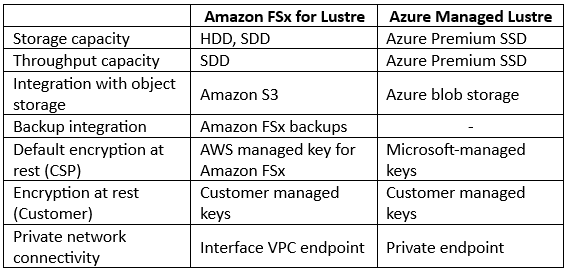

Comparison between File storage for HPC workloads alternatives:

Summary

Persistent storage is required by almost any workload, including cloud-native applications.

In this blog post, we have reviewed the various managed storage options offered by the hyperscale cloud providers.

As best practice, it is crucial to understand the application’s requirements, when selecting the right storage option.

About the Author

Eyal Estrin is a cloud and information security architect, and the author of the books Cloud Security Handbook and Security for Cloud Native Applications, with more than 20 years in the IT industry.

You can connect with him on social media (https://linktr.ee/eyalestrin).

Opinions are his own and not the views of his employer.

👇Help to support my authoring👇

☕ Buy me a coffee ☕

Poor architecture decisions when migrating to the cloud

When organizations are designing their first workload migrations to the cloud, they tend to mistakenly look at the public cloud as the promised land that will solve all their IT challenges (from scalability, availability, cost, and more).

In the way to achieve their goals, organizations tend to make poor architectural decisions.

In this blog post, we will review some of the common architectural mistakes made by organizations.

Lift and Shift approach

Migrating legacy monolithic workload from the on-premises and moving it as is to the public cloud might work (unless you have a license or specific hardware requirements), but it will result in poor outcomes.

Although VMs can run perfectly well in the cloud, most of the chances you will have to measure the performance of the VMs over time and right-size the instances to match the actual running workload to match customers’ demand.

The lift and shift approach is suitable as an interim solution until the organization has the time and resources to re-architect the workload, and perhaps choose a different architecture (for example migrate from VMs to containers or even Serverless).

In the long run, lift and shift will be a costly solution (compared to the on-premises) and will not be able to gain the full capabilities of the cloud (such as horizontal scale, scale to zero, resiliency of managed services, and more).

Using Kubernetes for small/simple workloads

When designing modern applications, organizations tend to follow industry trends.

One of the hottest trends is to choose containers for deploying various application components, and in many cases, organizations choose Kubernetes as the container orchestrator engine.

Although Kubernetes does have many benefits, and all hyper-scale cloud providers offer a managed Kubernetes control plane, Kubernetes creates many challenges.

The learning curve for fully understanding how to configure and maintain Kubernetes is very long.

For small or predictable applications, built from a small number of different containers, there are better and easy-to-deploy and maintain alternatives, such as Amazon ECS, Azure Container Apps, or Google Cloud Run — all of them are fully capable of running production workloads, and are much easier to learn and maintain then Kubernetes.

Using cloud storage for backup or DR scenarios

When organizations began to search for their first use cases for using the public cloud, they immediately thought about using cloud storage as a backup location or perhaps even for DR scenarios.

Although both use cases are valid options, they both tend to miss the bigger picture.

Even if we use object storage (or managed NFS/CIFS storage services) for the organization’s backup site, we must always take into consideration the restore phase.

Large binary backup files that we need to pull from the cloud environment back to on-premises will take a lot of time, not to mention the egress data cost, the read object API calls cost, and more.

The same goes with DR scenarios — if we back up our on-premises VMs or even databases to the cloud, if we don’t have a similar infrastructure environment in the cloud, what will a cold DR site assist us in case of a catastrophic disaster?

Separating between the application and the back-end data-store tiers

Most applications are built from a front-end/application tier and a back-end persistent storage tier.

In a legacy or tightly coupled architecture, there is a requirement for low latency between the application tier and the data store tier, specifically when reading or writing to a backend database.

A common mistake is creating a hybrid architecture, where the front-end is in the cloud, pulling data from an on-prem database, or an architecture (rare scenario) where a legacy on-prem application is connecting to a managed database service in the cloud.

Unless the target application is not prone to network latency, it is always recommended to architect all components close to each other, decreasing the network latency between the various application components.

Going multi-cloud in the hope of resolving vendor lock-in risk

A common risk many organizations looking into is vendor lock-in (i.e., customers being locked into the ecosystem of a specific cloud provider).

When digging into this risk, vendor lock-in is about the cost of switching between cloud providers.

Multi-cloud will not resolve the risk, but it will create many more challenges, from skills gap (teams familiar with different cloud providers ecosystems), central identity and access management, incident response over multiple cloud environments, egress traffic cost, and more.

Instead of designing complex architectures to mitigate theoretical or potential risk, design solutions to meet the business needs, familiarize yourself with a single public cloud provider’s ecosystem, and over time, once your teams have enough knowledge about more than a single cloud provider, expand your architecture — don’t run to multi-cloud from day 1.

Choosing the cheapest region in the cloud

As a rule of thumb, unless you have a specific data residency requirement, choose a region close to your customers, to lower the network latency.

Cost is an important factor, but you should design an architecture where your application and data reside close to customers.

If your application serves customers all around the globe, or in multiple locations, consider adding a CDN layer to keep all static content closer to your customers, combined with multi-region solutions (such as cross-region replication, global databases, global load-balancers, etc.)

Failing to re-assess the existing architecture

In the traditional data center, we used to design an architecture for the application and keep it static for the entire lifecycle of the application.

When designing modern applications in the cloud, we should embrace a dynamic mindset, meaning keep re-assessing the architecture, look at past decisions, and see if new technologies or new services can provide more suitable solutions for running the application.

The dynamic nature of the cloud, combined with evolving technologies, provides us with the ability to make changes and better ways to run applications faster, more resilient, and in a cost-effective manner.

Bias architecture decisions

This is a pitfall that many architects fall into — coming with a background in a specific cloud provider, and designing architectures around this cloud provider’s ecosystem, embedding bias decisions and service limitations into architecture design.

Instead, architects should fully understand the business needs, the entire spectrum of cloud solutions, service costs, and limitations, and only then begin to choose the most appropriate services, to take part in the application’s architecture.

Failure to add cost to architectural decisions

Cost is a huge factor when consuming cloud services, among the main reasons is the ability to consume services on demand (and stop paying for unused services).

Each decision you are making (from selecting the right compute nodes, storage tier, database tier, and more), has its cost impact.

Once we understand each service pricing model, and the specific workload potential growth, we can estimate the potential cost.

As we previously mentioned, the dynamic nature of the cloud might cause different costs each month, and as a result, we need to keep evaluating the service cost regularly, replace services from time to time, and adjust it to suit the specific workload.

Summary

The public cloud has many challenges in picking the right services and architectures to meet specific workload requirements and use cases.

Although there is no right or wrong answer when designing architecture, in this blog post, we have reviewed many “poor” architectural decisions that can be avoided by looking at the bigger picture and designing for the long term, instead of looking at short-term solutions.

Recommendation for the post readers — keep expanding your knowledge in cloud and architecture-related technologies, and keep questioning your current architectures, to see over time, if there are more suitable alternatives for your past decisions.

About the Author

Eyal Estrin is a cloud and information security architect, and the author of the books Cloud Security Handbook and Security for Cloud Native Applications, with more than 20 years in the IT industry. You can connect with him on social media (https://linktr.ee/eyalestrin).

Opinions are his own and not the views of his employer.

Checklist for designing cloud-native applications – Part 2: Security aspects

This post was originally published by the Cloud Security Alliance.

In Chapter 1 of this series about considerations when building cloud-native applications, we introduced various topics such as business requirements, infrastructure considerations, automation, resiliency, and more.

In this chapter, we will review security considerations when building cloud-native applications.

IAM Considerations – Authentication

Identity and Access Management plays a crucial role when designing new applications.

We need to ask ourselves – Who are our customers?

If we are building an application that will serve internal customers, we need to make sure our application will be able to sync identities from our identity provider (IdP).

On the other hand, if we are planning an application that will serve external customers, in most cases we would not want to manage the identities themselves, but rather allow authentication based on SAML, OAuth, or OpenID connect, and manage the authorization in our application.

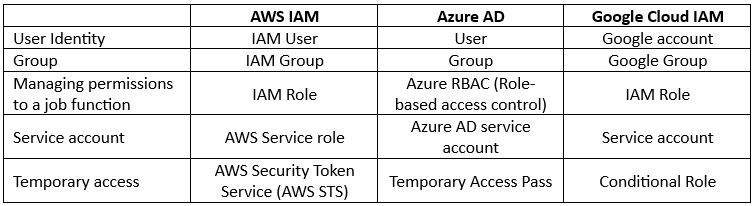

Examples of managed cloud-native identity services: AWS IAM Identity Center, Microsoft Entra ID, and Google Cloud Identity.

IAM Considerations – Authorization

Authorization is also an important factor when designing applications.

When our application consumes services (such as compute, storage, database, etc.) from a CSP ecosystem, each CSP has its mechanisms to manage permissions to access services and take actions, and each CSP has its way of implementing Role-based access control (RBAC).

Regardless of the built-in mechanisms to consume cloud infrastructure, we must always follow the principle of least privilege (i.e., minimal permissions to achieve a task).

On the application layer, we need to design an authorization mechanism to check each identity that was authenticated to our application, against an authorization engine (interactive authentication, non-interactive authentication, or even API-based access).

Although it is possible to manage authorization using our own developed RBAC mechanism, it is time to consider more cloud-agnostic authorization policy engines such as Open Policy Agent (OPA).

One of the major benefits of using OPA is the fact that its policy engine is not limited to authorization to an application – you can also use it for Kubernetes authorization, for Linux (using PAM), and more.

Policy-as-Code Considerations

Policy-as-Code allows you to configure guardrails on various aspects of your workload.

Guardrails are offered by all major cloud providers, outside the boundary of a cloud account, and impact the maximum allowed resource consumption or configuration.

Examples of guardrails:

- Limitation on the allowed region for deploying resources (compute, storage, database, network, etc.)

- Enforce encryption at rest

- Forbid the ability to create publicly accessible resources (such as a VM with public IP)

- Enforce the use of specific VM instance size (number of CPUs and memory allowed)

Guardrails can also be enforced as part of a CI/CD pipeline when deploying resources using Infrastructure as Code for automation purposes – The IaC code is been evaluated before the actual deployment phase, and assuming the IaC code does not violate the Policy as Code, resources are been updated.

Examples of Policy-as-Code: AWS Service control policies (SCPs), Azure Policy, Google Organization Policy Service, HashiCorp Sentinel, and Open Policy Agent (OPA).

Data Protection Considerations

Almost any application contains valuable data, whether the data has business or personal value, and as such we must protect the data from unauthorized parties.

A common way to protect data is to store it in encrypted form:

- Encryption in transit – done using protocols such as TLS (where the latest supported version is 1.3)

- Encryption at rest – done on a volume, disk, storage, or database level, using algorithms such as AES

- Encryption in use – done using hardware supporting a trusted execution environment (TEE), also referred to as confidential computing

When encrypting data we need to deal with key generation, secured vault for key storage, key retrieval, and key destruction.

All major CSPs have their key management service to handle the entire key lifecycle.

If your application is deployed on top of a single CSP infrastructure, prefer to use managed services offered by the CSP.

For encryption in use, select services (such as VM instances or Kubernetes worker nodes) that support confidential computing.

Secrets Management Considerations

Secrets are equivalent to static credentials, allowing access to services and resources.

Examples of secrets are API keys, passwords, database credentials, etc.

Secrets, similarly to encryption keys, are sensitive and need to be protected from unauthorized parties.

From the initial application design process, we need to decide on a secured location to store secrets.

All major CSPs have their own secrets management service to handle the entire secret’s lifecycle.

As part of a CI/CD pipeline, we should embed an automated scanning process to detect secrets embedded as part of code, scripts, and configuration files, to avoid storing any secrets as part of our application (i.e., outside the secured secrets management vault).

Examples of secrets management services: AWS Secrets Manager, Azure Key Vault, Google Secret Manager, and HashiCorp Vault.

Network Security Considerations

Applications must be protected at the network layer, whether we expose our application to internal customers or customers over the public internet.

The fundamental way to protect infrastructure at the network layer is using access controls, which are equivalent to layer 3/layer 4 firewalls.

All CSPs have access control mechanisms to restrict access to services (from access to VMs, databases, etc.)

Examples of Layer 3 / Layer 4 managed services: AWS Security groups, Azure Network security groups, and Google VPC firewall rules.

Some cloud providers support private access to their services, by adding a network load-balancer in front of various services, with an internal IP from the customer’s private subnet, enforcing all traffic to pass inside the CSP’s backbone, and not over the public internet.

Examples of private connectivity solutions: AWS PrivateLink, Azure Private Link, and Google VPC Service Controls.

Some of the CSPs offer managed layer 7 firewalls, allowing customers to enforce traffic based on protocols (and not ports), inspecting TLS traffic for malicious content, and more, in case your application or business requires those capabilities.

Examples of Layer 7 managed firewalls: AWS Network Firewall, Azure Firewall, and Google Cloud NGFW.

Application Layer Protection Considerations

Any application accessible to customers (internal or over the public Internet), is exposed to application layer attacks.

Attacks can range from malicious code injection, data exfiltration (or data leakage), data tampering, unauthorized access, and more.

Whether you are exposing an API, a web application, or a mobile application, it is important to implement application layer protection, such as a WAF service.

All major CSPs offer managed WAF services, and there are many SaaS solutions by commercial vendors that offer managed WAF services.

Examples of managed WAF services: AWS WAF, Azure WAF, and Google Cloud Armor.

DDoS Protection Considerations

Denial-of-Service (DoS) or Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) is a risk for any service accessible over the public Internet.

Such attacks try to consume all the available resources (from network bandwidth to CPU/memory), directly impacting the service availability to be accessible by customers.

All major CSPs offer managed DDoS protection services, and there are many DDoS protection solutions by commercial vendors that offer managed DDoS protection services.

Examples of managed DDoS protection services: AWS Shield, Azure DDoS Protection, Google Cloud Armor, and Cloudflare DDoS protection.

Patch Management Considerations

Software tends to be vulnerable, and as such it must be regularly patched.

For applications deployed on top of virtual machines:

- Create a “golden image” of a virtual machine, and regularly update the image with the latest security patches and software updates.

- For applications deployed on top of VMs, create a regular patch update process.

For applications wrapped inside containers, create a “golden image” of each of the application components, and regularly update the image with the latest security patches and software updates.

Embed software composition analysis (SCA) tools to scan and detect vulnerable third-party components – in case vulnerable components (or their dependencies) are detected, begin a process of replacing the vulnerable components.

Examples of patch management solutions: AWS Systems Manager Patch Manager, Azure Update Manager, and Google VM Manager Patch.

Compliance Considerations

Compliance is an important security factor when designing an application.

Some applications contain personally identifiable information (PII) about employees or customers, which requires compliance against privacy and data residency laws and regulations (such as the GDPR in Europe, the CPRA in California, the LGPD in Brazil, etc.)

Some organizations decide to be compliant with industry or security best practices, such as the Center for Internet Security (CIS) Benchmark for hardening infrastructure components, and can be later evaluated using compliance services or Cloud security posture management (CSPM) solutions.

References for compliance: AWS Compliance Center, Azure Service Trust Portal, and Google Compliance Resource Center.

Incident Response

When designing an application in the cloud, it is important to be prepared to respond to security incidents:

- Enable logging from both infrastructure and application components, and stream all logs to a central log aggregator. Make sure logs are stored in a central, immutable location, with access privileges limited for the SOC team.

- Select a tool to be able to review logs, detect anomalies, and be able to create actionable insights for the SOC team.

- Create playbooks for the SOC team, to know how to respond in case of a security incident (how to investigate, where to look for data, who to notify, etc.)

- To be prepared for a catastrophic event (such as a network breach, or ransomware), create automated solutions, to allow you to quarantine the impacted services, and deploy a new environment from scratch.

References for incident response documentation: AWS Security Incident Response Guide, Azure Incident response, and Google Data incident response process.

Summary

In the second blog post in this series, we talked about many security-related aspects, that organizations should consider when designing new applications in the cloud.

In this part of the series, we have reviewed various aspects, from identity and access management to data protection, network security, patch management, compliance, and more.

It is highly recommended to use the topics discussed in this series of blog posts, as a baseline when designing new applications in the cloud, and continuously improve this checklist of considerations when documenting your projects.

About the Author

Eyal Estrin is a cloud and information security architect, and the author of the book Cloud Security Handbook, with more than 20 years in the IT industry. You can connect with him on Twitter.

Opinions are his own and not the views of his employer.

Checklist for designing cloud-native applications – Part 1: Introduction

This post was originally published by the Cloud Security Alliance.

When organizations used to build legacy applications in the past, they used to align infrastructure and application layers to business requirements, reviewing hardware requirements and limitations, team knowledge, security, legal considerations, and more.

In this series of blog posts, we will review considerations when building today’s cloud-native applications.

Readers of this series of blog posts can use the information shared, as a checklist to be embedded as part of a design document.

Introduction

Building a new application requires a thorough design process.

It is ok to try, fail, and fix mistakes during the process, but you still need to design.

Since technology keeps evolving, new services are released every day, and many organizations now begin using multiple cloud providers, it is crucial to avoid biased decisions.

During the design phase, avoid locking yourself to a specific cloud provider, instead, fully understand the requirements and constraints, and only then begin selecting the technology and services you will be using to architect your application’s workload.

Business Requirements

The first thing we need to understand is what is the business goal. What is the business trying to achieve?

Business requirements will impact architectural decisions.

Below are some of the common business requirements:

- Service availability – If an application needs to be available for customers around the globe, design a multi-region architecture.

- Data sovereignty – If there is a regulatory requirement to store customers data in a specific country, make sure it is possible to deploy all infrastructure components in a cloud region located in a specific country. Examples of data sovereignty services: AWS Digital Sovereignty, Microsoft Cloud for Sovereignty, and Google Digital Sovereignty

- Response time – If the business requirement is to allow fast response to customer requests, you may consider the use of API or caching mechanisms.

- Scalability – If the business requirement is to provide customers with highly scalable applications, to be able to handle unpredictable loads, you may consider the use of event-driven architecture (such as the use of message queues, streaming services, and more)

Compute Considerations

Compute may be the most important part of any modern application, and today there are many alternatives for running the front-end and business logic of our applications:

- Virtual Machines – Offering the same alternatives as we used to run legacy applications on-premise, but can also be suitable for running applications in the cloud. For most cases, use VMs if you are migrating an application from on-premise to the cloud. Examples of services: Amazon EC2, Azure Virtual Machines, and Google Compute Engine.

- Containers and Kubernetes – Most modern applications are wrapped inside containers, and very often are scheduled using Kubernetes orchestrator. Considered as a medium challenge migrating container-based workloads between cloud providers (you still need to take under consideration the integration with other managed services in the CSPs eco-system). Examples of Kubernetes services: Amazon EKS, Azure AKS, and Google GKE.

- Serverless / Functions-as-a-Service – Modern way to run various parts of applications. The underlying infrastructure is fully managed by the cloud provider (no need to deal with scaling or maintenance of the infrastructure). Considered as a vendor lock-in since there is no way to migrate between CSPs, due to the unique characteristics of each CSP’s offering. Examples of FaaS: AWS Lambda, Azure Functions, and Google Cloud Functions.

Data Store Considerations

Most applications require a persistent data store, for storing and retrieval of data.

Cloud-native applications (and specifically microservice-based architecture), allow selecting the most suitable back-end data store for your applications.

In a microservice-based architecture, you can select different data stores for each microservice.

Alternatives for persistent data can be:

- Object storage – The most common managed storage service that most cloud applications are using to store data (from logs, archives, data lake, and more). Examples of object storage services: Amazon S3, Azure Blob Storage, and Google Cloud Storage.

- File storage – Most CSPs support managed NFS services (for Unix workloads) or SMB/CIFS (for Windows workloads). Examples of file storage services: Amazon EFS, Azure Files, and Google Filestore.

When designing an architecture, consider your application requirements such as:

- Fast data retrieval requirements – Requirements for fast read/write (measures in IOPS)

- File sharing requirements – Ability to connect to the storage from multiple sources

- Data access pattern – Some workloads require constant access to the storage, while other connects to the storage occasionally, (such as file archive)

- Data replication – Ability to replicate data over multiple AZs or even multiple regions

Database Considerations

It is very common for most applications to have at least one backend database for storing and retrieval of data.

When designing an application, understand the application requirements to select the most suitable database:

- Relational database – Database for storing structured data stored in tables, rows, and columns. Suitable for complex queries. When selecting a relational database, consider using a managed database that supports open-source engines such as MySQL or PostgreSQL over commercially licensed database engine (to decrease the chance of vendor lock-in). Examples of relational database services: Amazon RDS, Azure SQL, and Google Cloud SQL.

- Key-value database – Database for storing structured or unstructured data, with requirements for storing large amounts of data, with fast access time. Examples of key-value databases: Amazon DynamoDB, Azure Cosmos DB, and Google Bigtable.

- In-memory database – Database optimized for sub-millisecond data access, such as caching layer. Examples of in-memory databases: Amazon ElastiCache, Azure Cache for Redis, and Google Memorystore for Redis.

- Document database – Database suitable for storing JSON documents. Examples of document databases: Amazon DocumentDB, Azure Cosmos DB, and Google Cloud Firestore.

- Graph database – Database optimized for storing and navigating relationships between entities (such as a recommendation engine). Example of Graph database: Amazon Neptune.

- Time-series database – Database optimized for storing and querying data that changes over time (such as application metrics, data from IoT devices, etc.). Examples of time-series databases: Amazon Timestream, Azure Time Series Insights, and Google Bigtable.

One of the considerations when designing highly scalable applications is data replication – the ability to replicate data across multiple AZs, but the more challenging is the ability to replicate data over multiple regions.

Few managed database services support global tables, or the ability to replicate over multiple regions, while most databases will require a mechanism for replicating database updates between regions.

Automation and Development

Automation allows us to perform repetitive tasks in a fast and predictable way.

Automation in cloud-native applications, allows us to create a CI/CD pipeline for taking developed code, integrating the various application components, and underlying infrastructure, performing various tests (from QA to securing tests) and eventually deploying new versions of our production application.

Whether you are using a single cloud provider, managing environments on a large scale, or even across multiple cloud providers, you should align the tools that you are using across the different development environments:

- Code repositories – Select a central place to store all your development team’s code, hopefully, it will allow you to use the same code repository for both on-prem and multiple cloud environments. Examples of code repositories: AWS CodeCommit, Azure Repos, and Google Cloud Source Repositories.

- Container image repositories – Select a central image repository, and sync it between regions, and if needed, also between cloud providers, to keep the same source of truth. Examples of container image repositories: Amazon ECR, Azure ACR, and Google Artifact Registry.

- CI/CD and build process – Select a tool to allow you to manage the CI/CD pipeline for all deployments, whether you are using a single cloud provider, or when using a multi-cloud environment. Examples of CI/CD build services: AWS CodePipeline, Azure Pipelines, and Google Cloud Build.

- Infrastructure as Code – Mature organizations choose an IaC tool to provision infrastructure for both single or multi-cloud scenarios, lowering the burden on the DevOps, IT, and developers’ teams. Examples of IaC: AWS CloudFormation, Azure Resource Manager, Google Cloud Deployment Manager, and HashiCorp Terraform.

Resiliency Considerations

Although many managed services in the cloud, are offered resilient by design by the cloud providers, consider resiliency when designing production applications.

Design all layers of the infrastructure to be resilient.

Regardless of the computing service you choose, always deploy VMs or containers in a cluster, behind a load-balancer.

Prefer to use a managed storage service, deployed over multiple availability zones.

For a persistent database, prefer a managed service, and deploy it in a cluster, over multiple AZs, or even better, look for a serverless database offer, so you won’t need to maintain the database availability.

Do not leave things to the hands of faith, embed chaos engineering experimentations as part of your workload resiliency tests, to have a better understanding of how your workload will survive a failure. Examples of managed chaos engineering services: AWS Fault Injection Service, and Azure Chaos Studio.

Business Continuity Considerations

One of the most important requirements from production applications is the ability to survive failure and continue functioning as expected.

It is crucial to design both business continuity in advance.

For any service that supports backups or snapshots (from VMs, databases, and storage services), enable scheduled backup mechanisms, and randomly test backups to make sure they are functioning.

For objects stored inside an object storage service that requires resiliency, configure cross-region replication.

For container registry that requires resiliency, configure image replication across regions.

For applications deployed in a multi-region architecture, use DNS records to allow traffic redirection between regions.

Observability Considerations

Monitoring and logging allow you insights into your application and infrastructure behavior.

Telemetry allows you to collect real-time information about your running application, such as customer experience.

While designing an application, consider all the options available for enabling logging, both from infrastructure services and from the application layer.

It is crucial to stream all logs to a central system, aggregated and timed synched.

Logging by itself is not enough – you need to be able to gain actionable insights, to be able to anticipate issues before they impact your customers.

It is crucial to define KPIs for monitoring an application’s performance, such as CPU/Memory usage, latency and uptime, average response time, etc.

Many modern tools are using machine learning capabilities to review large numbers of logs, be able to correlate among multiple sources and provide recommendations for improvements.

Cost Considerations

Cost is an important factor when designing architectures in the cloud.

As such, it must be embedded in every aspect of the design, implementation, and ongoing maintenance of the application and its underlying infrastructure.

Cost aspects should be the responsibility of any team member (IT, developers, DevOps, architect, security staff, etc.), from both initial service cost and operational aspects.

FinOps mindset will allow making sure we choose the right service for the right purpose – from choosing the right compute service, the right data store, or the right database.

It is not enough to select a service –make sure any service selected is tagged, monitored for its cost regularly, and perhaps even replaced with better and cost-effective alternatives, during the lifecycle of the workload.

Sustainability Considerations

The architectural decision we make has an environmental impact.

When developing modern applications, consider the environmental impact.

Choosing the right computing service will allow running a workload, with a minimal carbon footprint – the use of containers or serverless/FaaS wastes less energy in the data centers of the cloud provider.

The same thing when selecting a datastore, according to an application’s data access patterns (from hot or real-time tier, up to archive tier).

Designing event-driven applications, adding caching layers, shutting down idle resources, and continuously monitoring workload resources, will allow to design of an efficient and sustainable workload.

Sustainability related references: AWS Sustainability, Azure Sustainability, and Google Cloud Sustainability.

Employee Knowledge Considerations

The easiest thing is to decide to build a new application in the cloud.

The challenging part is to make sure all teams are aligned in terms of the path to achieving business goals and the knowledge to build modern applications in the cloud.

Organizations should invest the necessary resources in employee training, making sure all team members have the required knowledge to build and maintain modern applications in the cloud.

It is crucial to understand that all team members have the necessary knowledge to maintain applications and infrastructure in the cloud, before beginning the actual project, to avoid unpredictable costs, long learning curves, while running in production, or building a non-efficient workload due to knowledge gap.

Training related references: AWS Skill Builder, Microsoft Learn for Azure, and Google Cloud Training.

Summary

In the first blog post in this series, we talked about many aspects, organizations should consider when designing new applications in the cloud.

In this part of the series, we have reviewed various aspects, from understanding business requirements to selecting the right infrastructure, automation, resiliency, cost, and more.

When creating the documentation for a new development project, organizations can use the information in this series, to form a checklist, making sure all-important aspects and decisions are documented.

In the next chapter of this series, we will discuss security aspects when designing and building a new application in the cloud.

About the Author

Eyal Estrin is a cloud and information security architect, and the author of the book Cloud Security Handbook, with more than 20 years in the IT industry. You can connect with him on Twitter.

Opinions are his own and not the views of his employer.

Building Resilient Applications in the Cloud

When building an application for serving customers, one of the questions raised is how do I know if my application is resilient and will survive a failure?

In this blog post, we will review what it means to build resilient applications in the cloud, and we will review some of the common best practices for achieving resilient applications.

What does it mean resilient applications?

AWS provides us with the following definition for the term resiliency:

“The ability of a workload to recover from infrastructure or service disruptions, dynamically acquire computing resources to meet demand, and mitigate disruptions, such as misconfigurations or transient network issues.”

Resiliency is part of the Reliability pillar for cloud providers such as AWS, Azure, GCP, and Oracle Cloud.

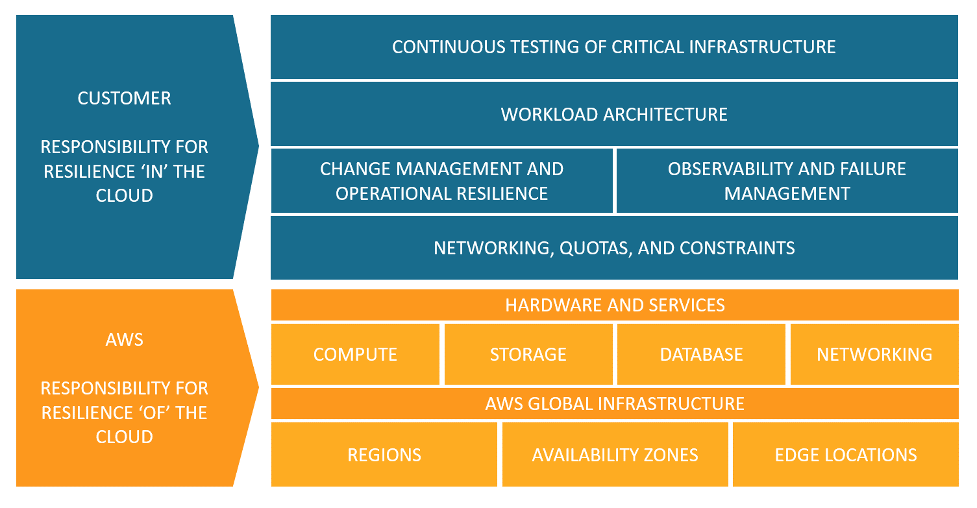

AWS takes it one step further, and shows how resiliency is part of the shared responsibility model:

- The cloud provider is responsible for the resilience of the cloud (i.e., hardware, software, computing, storage, networking, and anything related to their data centers)

- The customer is responsible for the resilience in the cloud (i.e., selecting the services to use, building resilient architectures, backup strategies, data replication, and more).

How do we build resilient applications?

This blog post assumes that you are building modern applications in the public cloud.

We have all heard of RTO (Recovery time objective).

Resilient workload (a combination of application, data, and the infrastructure that supports it), should not only recover automatically, but it must recover within a pre-defined RTO, agreed by the business owner.

Below are common best practices for building resilient applications:

Design for high-availability

The public cloud allows you to easily deploy infrastructure over multiple availability zones.

Examples of implementing high availability in the cloud:

- Deploying multiple VMs behind an auto-scaling group and a front-end load-balancer

- Spreading container load over multiple Kubernetes worker nodes, deploying in multiple AZs

- Deploying a cluster of database instances in multiple AZs

- Deploying global (or multi-regional) database services (such as Amazon Aurora Global Database, Azure Cosmos DB, Google Cloud Spanner, and Oracle Global Data Services (GDS)

- Configure DNS routing rules to send customers’ traffic to more than a single region

- Deploy global load-balancer (such as AWS Global Accelerator, Azure Cross-region Load Balancer, or Google Global external Application Load Balancer) to spread customers’ traffic across regions

Implement autoscaling

Autoscaling is one of the biggest advantages of the public cloud.

Assuming we built a stateless application, we can add or remove additional compute nodes using autoscaling capability, and adjust it to the actual load on our application.

In a cloud-native infrastructure, we will use a managed load-balancer service, to receive traffic from customers, and send an API call to an autoscaling group, to add or remove additional compute nodes.

Implement microservice architecture

Microservice architecture is meant to break a complex application into smaller parts, each responsible for certain functionality of the application.

By implementing microservice architecture, we are decreasing the impact of failed components on the rest of the application.

In case of high load on a specific component, it is possible to add more compute resources to the specific component, and in case we discover a bug in one of the microservices, we can roll back to a previous functioning version of the specific microservice, with minimal impact on the rest of the application.

Implement event-driven architecture

Event-driven architecture allows us to decouple our application components.

Resiliency can be achieved using event-driven architecture, by the fact that even if one component fails, the rest of the application continues to function.

Components are loosely coupled by using events that trigger actions.

Event-driven architectures are usually (but not always) based on services managed by cloud providers, who are responsible for the scale and maintenance of the managed infrastructure.

Event-driven architectures are based on models such as pub/sub model (services such as Amazon SQS, Azure Web PubSub, Google Cloud Pub/Sub, and OCI Queue service) or based on event delivery (services such as Amazon EventBridge, Azure Event Grid, Google Eventarc, and OCI Events service).

Implement API Gateways

If your application exposes APIs, use API Gateways (services such as Amazon API Gateway, Azure API Management, Google Apigee, or OCI API Gateway) to allow incoming traffic to your backend APIs, perform throttling to protect the APIs from spikes in traffic, and perform authorization on incoming requests from customers.

Implement immutable infrastructure

Immutable infrastructure (such as VMs or containers) are meant to run application components, without storing session information inside the compute nodes.

In case of a failed component, it is easy to replace the failed component with a new one, with minimal disruption to the entire application, allowing to achieve fast recovery.

Data Management

Find the most suitable data store for your workload.

A microservice architecture allows you to select different data stores (from object storage to backend databases) for each microservice, decreasing the risk of complete failure due to availability issues in one of the backend data stores.

Once you select a data store, replicate it across multiple AZs, and if the business requires it, replicate it across multiple regions, to allow better availability, closer to the customers.

Implement observability

By monitoring all workload components, and sending logs from both infrastructure and application components to a central logging system, it is possible to identify anomalies, anticipate failures before they impact customers, and act.

Examples of actions can be sending a command to restart a VM, deploying a new container instead of a failed one, and more.

It is important to keep track of measurements — for example, what is considered normal response time to a customer request, to be able to detect anomalies.

Implement chaos engineering

The base assumption is that everything will eventually fail.

Implementing chaos engineering, allows us to conduct controlled experiments, inject faults into our workloads, testing what will happen in case of failure.

This allows us to better understand if our workload will survive a failure.

Examples can be adding load on disk volumes, injecting timeout when an application tier connects to a backend database, and more.

Examples of services for implementing chaos engineering are AWS Fault Injection Simulator, Azure Chaos Studio, and Gremlin.

Create a failover plan

In an ideal world, your workload will be designed for self-healing, meaning, it will automatically detect a failure and recover from it, for example, replace failed components, restart services, or switch to another AZ or even another region.

In practice, you need to prepare a failover plan, keep it up to date, and make sure your team is trained to act in case of major failure.

A disaster recovery plan without proper and regular testing is worth nothing — your team must practice repeatedly, and adjust the plan, and hopefully, they will be able to execute the plan during an emergency with minimal impact on customers.

Resilient applications tradeoffs

Failure can happen in various ways, and when we design our workload, we need to limit the blast radius on our workload.

Below are some common failure scenarios, and possible solutions:

- Failure in a specific component of the application — By designing a microservice architecture, we can limit the impact of a failed component to a specific area of our application (depending on the criticality of the component, as part of the entire application)

- Failure or a single AZ — By deploying infrastructure over multiple AZs, we can decrease the chance of application failure and impact on our customers

- Failure of an entire region — Although this scenario is rare, cloud regions also fail, and by designing a multi-region architecture, we can decrease the impact on our customers

- DDoS attack — By implementing DDoS protection mechanisms, we can decrease the risk of impacting our application with a DDoS attack

Whatever solution we design for our workloads, we need to understand that there is a cost and there might be tradeoffs for the solution we design.

Multi-region architecture aspects

A multi-region architecture will allow the most highly available resilient solution for your workloads; however, multi-region adds high cost for cross-region egress traffic, most services are limited to a single region, and your staff needs to know to support such a complex architecture.

Another limitation of multi-region architecture is data residency — if your business or regulator demands that customers’ data be stored in a specific region, a multi-region architecture is not an option.

Service quota/service limits

When designing a highly resilient architecture, we must take into consideration service quotas or service limits.

Sometimes we are bound to a service quota on a specific AZ or region, an issue that we may need to resolve with the cloud provider’s support team.

Sometimes we need to understand there is a service limit in a specific region, such as a specific service that is not available in a specific region, or there is a shortage of hardware in a specific region.

Autoscaling considerations

Horizontal autoscale (the ability to add or remove compute nodes) is one of the fundamental capabilities of the cloud, however, it has its limitations.

Provisioning a new compute node (from a VM, container instance, or even database instance) may take a couple of minutes to spin up (which may impact customer experience) or to spin down (which may impact service cost).

Also, to support horizontal scaling, you need to make sure the compute nodes are stateless, and that the application supports such capability.

Failover considerations

One of the limitations of database failover is their ability to switch between the primary node and one of the secondary nodes, either in case of failure or in case of scheduled maintenance.

We need to take into consideration the data replication, making sure transactions were saved and moved from the primary to the read replica node.

Summary

In this blog post, we have covered many aspects of building resilient applications in the cloud.

When designing new applications, we need to understand the business expectations (in terms of application availability and customer impact).

We also need to understand the various architectural design considerations, and their tradeoffs, to be able to match the technology to the business requirements.

As I always recommend — do not stay on the theoretical side of the equation, begin designing and building modern and highly resilient applications to serve your customers — There is no replacement for actual hands-on experience.

References

- Understand resiliency patterns and trade-offs to architect efficiently in the cloud

- Building resilience to your business requirements with Azure

- Success through culture: why embracing failure encourages better software delivery

- Building Resilient Solutions in OCI

About the Author

Eyal Estrin is a cloud and information security architect, and the author of the book Cloud Security Handbook, with more than 20 years in the IT industry. You can connect with him on Twitter.

Opinions are his own and not the views of his employer.

Why choosing “Lift & Shift” is a bad migration strategy

One of the first decisions organizations make before migrating applications to the public cloud is deciding on a migration strategy.

For many years, the most common and easy way to migrate applications to the cloud was choosing a rehosting strategy, also known as “Lift and shift”.

In this blog post, I will review some of the reasons, showing that strategically this is a bad decision.

Introduction

When reviewing the landscape of possibilities for migrating legacy or traditional applications to the public cloud, rehosting is the best option as a short-term solution.

Taking an existing monolith application, and migrating it as-is to the cloud, is supposed to be an easy task:

- Map all the workload components (hardware requirements, operating system, software and licenses, backend database, etc.)

- Choose similar hardware (memory/CPU/disk space) to deploy a new VM instance(s)

- Configure network settings (including firewall rules, load-balance configuration, DNS, etc.)

- Install all the required software components (assuming no license dependencies exist)

- Restore the backend database from the latest full backup

- Test the newly deployed application in the cloud

- Expose the application to customers

From a time and required-knowledge perspective, this is considered a quick-win solution, but how efficient is it?

Cost-benefit

Using physical or even virtual machines does not guarantee us close to 100% of hardware utilization.

In the past organizations used to purchase hardware, and had to commit to 3–5 years (for vendor support purposes).

Although organizations could use the hardware 24×7, there were many cases where purchased hardware was consuming electricity and floor-space, without running at full capacity (i.e., underutilized).

Virtualization did allow organizations to run multiple VMs on the same physical hardware, but even then, it did not guarantee 100% hardware utilization — think about Dev/Test environments or applications that were not getting traffic from customers during off-peak hours.

The cloud offers organizations new purchase/usage methods (such as on-demand or Spot), allowing customers to pay just for the time they used compute resources.

Keeping a traditional data-center mindset, using virtual machines, is not efficient enough.

Switching to modern ways of running applications, such as the use of containers, Function-as-a-Service (FaaS), or event-driven architectures, allows organizations to make better use of their resources, at much better prices.

Right-sizing

On day 1, it is hard to predict the right VM instance size for the application.

When migrating applications as-is, organizations tend to select similar hardware (mostly CPU/Memory), to what they used to have in the traditional data center, regardless of the application’s actual usage.

After a legacy application is running for several weeks in the cloud, we can measure its actual performance, and switch to a more suitable VM instance size, gaining better utilization and price.

Tools such as AWS Compute Optimizer, Azure Advisor, or Google Recommender will allow you to select the most suitable VM instance size, but the VM still does not utilize 100% of the possible compute resources, compared to containers or Function-as-a-Service.

Scaling

Horizontal scaling is one of the main benefits of the public cloud.

Although it is possible to configure multiple VMs behind a load-balancer, with autoscaling capability, allowing adding or removing VMs according to the load on the application, legacy applications may not always support horizontal scaling, and even if they do support scale out (add more compute nodes), there is a very good chance they do not support scale in (removing unneeded compute nodes).

VMs do not support the ability to scale to zero — i.e., removing completely all compute nodes, when there is no customer demand.

Cloud-native applications deployed on top of containers, using a scheduler such as Kubernetes (such as Amazon EKS, Azure AKS, or Google GKE), can horizontally scale according to need (scale out as much as needed, or as many compute resources the cloud provider’s quota allows).

Functions as part of FaaS (such as AWS Lambda, Azure Functions, or Google Cloud Functions) are invoked as a result of triggers, and erased when the function’s job completes — maximum compute utilization.

Load time

Spinning up a new VM as part of auto-scaling activity (such as AWS EC2 Auto Scaling, Azure Virtual Machine Scale Sets, or Google Managed instance groups), upgrade, or reboot takes a long time — specifically for large workloads such as Windows VMs, databases (deployed on top of VM’s) or application servers.

Provisioning a new container (based on Linux OS), including all the applications and layers, takes a couple of seconds (depending on the number of software layers).

Invoking a new function takes a few seconds, even if you take into consideration cold start issues when downloading the function’s code.

Software maintenance

Every workload requires ongoing maintenance — from code upgrades, third-party software upgrades, and let us not forget security upgrades.

All software upgrade requires a lot of overhead from the IT, development, and security teams.

Performing upgrades of a monolith, where various components and services are tightly coupled together increases the complexity and the chances that something will break.

Switching to a microservice architecture, allows organizations to upgrade specific components (for example scale out, upgrade new version of code, new third-party software component), with small to zero impact on other components of the entire application.

Infrastructure maintenance

In the traditional data center, organizations used to deploy and maintain every component of the underlying infrastructure supporting the application.

Maintaining services such as databases or even storage arrays requires a dedicated trained staff, and requires a lot of ongoing efforts (from patching, backup, resiliency, high availability, and more).

In cloud-native environments, organizations can take advantage of managed services, from managed databases, storage services, caching, monitoring, and AI/ML services, without having to maintain the underlying infrastructure.

Unless an application relies on a legacy database engine, most of the chance, you will be able to replace a self-maintained database server, with a managed database service.

For storage services, most cloud providers already offer all the commodity storage services (from a managed NFS, SMB/CIFS, NetApp, and up to parallel file system for HPC workloads).

Most modern cloud-native services, use object storage services (such as Amazon S3, Azure Blob Storage, or Google Filestore), allowing scalable file systems for storing large amounts of data (from backups, and log files to data lake).

Most cloud providers offer managed networking services for load-balancing, firewalls, web application firewalls, and DDoS protection mechanisms, supporting workloads with unpredictable traffic.

SaaS services

Up until now, we mentioned lift & shift from the on-premise to VMs (mostly IaaS) and managed services (PaaS), but let us not forget there is another migration strategy — repurchasing, meaning, migrating an existing application, or selecting a managed platform such as Software-as-a-Service, allowing organizations to consume fully managed services, without having to take care of the on-going maintenance and resiliency.

Summary

Keeping a static data center mindset, and migrating using “lift & shift” to the public cloud, is the least cost-effective strategy and in most chances will end up with medium to low performance for your applications.

It may have been the common strategy a couple of years ago when organizations just began taking their first step in the public cloud, but as more knowledge is gained from both public cloud providers and all sizes of organizations, it is time to think about more mature cloud migration strategies.

It is time for organizations to embrace a dynamic mindset of cloud-native services and cloud-native applications, which provide organizations many benefits, from (almost) infinite scale, automated provisioning (using Infrastructure-as-Code), rich cloud ecosystem (with many managed services), and (if managed correctly) the ability to suit the workload costs to the actual consumption.

I encourage all organizations to expand their knowledge about the public cloud, assess their existing applications and infrastructure, and begin modernizing their existing applications.

Re-architecture may demand a lot of resources (both cost and manpower) in the short term but will provide an organization with a lot of benefits in the long run.

References:

- 6 Strategies for Migrating Applications to the Cloud

- Overview of application migration examples for Azure

- Migrate to Google Cloud

About the Author

Eyal Estrin is a cloud and information security architect, and the author of the book Cloud Security Handbook, with more than 20 years in the IT industry. You can connect with him on Twitter.

Opinions are his own and not the views of his employer.

Introduction to Serverless Container Services

When developing modern applications, we almost immediately think about wrapping our application components inside Containers — it may not be the only architectural alternative, but a very common one.

Assuming our developers and DevOps teams have the required expertise to work with Containers, we still need to think about maintaining the underlying infrastructure — i.e., the Container hosts.

If our application has a steady and predictable load, and assuming we do not have experience maintaining Kubernetes clusters, and we do not need the capabilities of Kubernetes, it is time to think about an easy and stable alternative for deploying our applications on top of Containers infrastructure.

In the following blog post, I will review the alternatives of running Container workloads on top of Serverless infrastructure.

Why do we need Serverless infrastructure for running Container workloads?

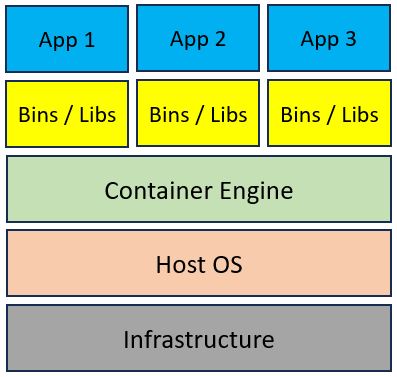

Container architecture is made of a Container engine (such as Docker, CRI-O, etc.) deployed on top of a physical or virtual server, and on top of the Container engine, we deploy multiple Container images for our applications.

The diagram below shows a common Container architecture:

If we focus on the Container engine and the underlying operating system, we understand that we still need to maintain the operating system itself.

Common maintenance tasks for the operating system:

- Make sure it has enough resources (CPU, memory, storage, and network connectivity) for running Containers

- Make sure the operating system is fully patched and hardened from external attacks

- Make sure our underlying infrastructure (i.e., Container host nodes), provides us with high availability in case one of the host nodes fails and needs to be replaced

- Make sure our underlying infrastructure provides us the necessary scale our application requires (i.e., scale out or in according to application load)

Instead of having to maintain the underlying host nodes, we should look for a Serverless solution, that allows us to focus on application deployment and maintenance and decrease as much as possible the work on maintaining the infrastructure.

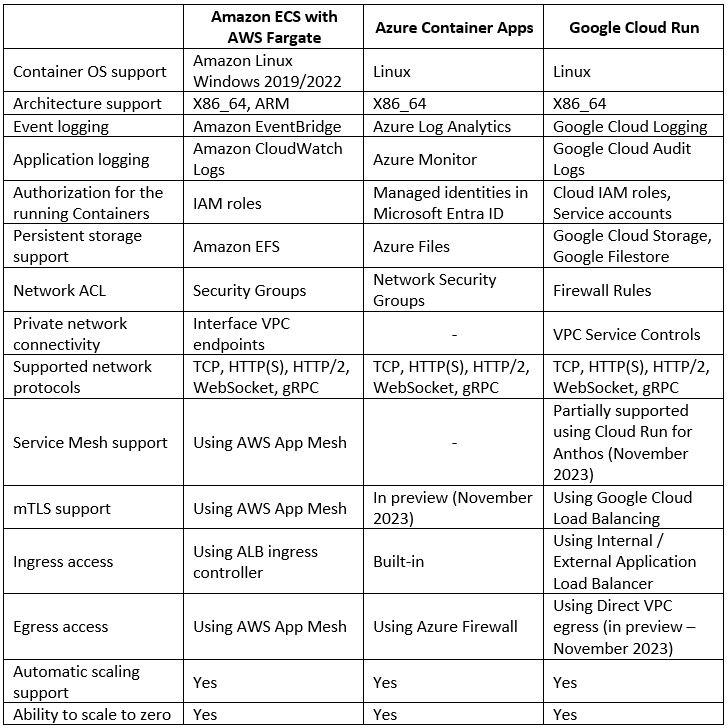

Comparison of Serverless Container Services

Each of the hyperscale cloud providers offers us the ability to consume a fully managed service for deploying our Container-based workloads.

Below is a comparison of AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud alternatives:

Side notes for Azure users

While researching for this blog post, I had a debate about whether to include Azure Containers Apps or Azure Container Instances.

Although both services allow customers to run Containers in a managed environment, Azure Container Instances is more suitable for running a single Container application, while Azure Container Apps allows customers to build a full microservice-based application.

Summary

In this blog post, I have compared alternatives for deploying microservice architecture on top of Serverless Container services offered by AWS, Azure, and GCP.

While designing your next application based on microservice architecture, and assuming you don’t need a full-blown Kubernetes cluster (with all of its features and complexities), consider using Serverless Container service.

References

About the Author

Eyal Estrin is a cloud and information security architect, and the author of the book Cloud Security Handbook, with more than 20 years in the IT industry. You can connect with him on Twitter.

Opinions are his own and not the views of his employer.

Introduction to Break-Glass in Cloud Environments

Using modern cloud environments, specifically production environments, decreases the need for human access.

It makes sense for developers to have access to Dev or Test environments, but in a properly designed production environment, everything should be automated – from deployment, and observability to self-healing. In most cases, no human access is required.

Production environments serve customers, require zero downtime, and in most cases contain customers’ data.

There are cases such as emergency scenarios where human access is required.

In mature organizations, this type of access is done by the Site reliability engineering (SRE) team.

The term break-glass is an analogy to breaking a glass to pull a fire alarm, which is supposed to happen only in case of emergency.

In the following blog post, I will review the different alternatives each of the hyperscale cloud providers gives their customers to handle break-glass scenarios.

Ground rules for using break-glass accounts

Before talking about how each of the hyperscale cloud providers handles break-glass, it is important to be clear – break-glass accounts should be used in emergency cases only.

- Authentication – All access through the break-glass mechanism must be authenticated, preferred against a central identity provider, and not using local accounts

- Authorization – All access must be authorized using role-based access control (RBAC), following the principle of least privilege

- MFA – Since most break-glass scenarios require highly privileged access, it is recommended to enforce multi-factor authentication (MFA) for any interactive access

- Just-in-time access – All access through break-glass mechanisms must be granted temporarily and must be revoked after a pre-define amount of time or when the emergency is declared as over

- Approval process – Access through a break-glass mechanism should be manually approved

- Auditing – All access through break-glass mechanisms must be audited and kept as evidence for further investigation

- Documented process – Organizations must have a documented and tested process for requesting, approving, using, and revoking break-glass accounts

Handling break-glass scenarios in AWS

Below is a list of best practices provided by AWS for handling break-glass scenarios:

Identity Management

Identities in AWS are managed using AWS Identity and Access Management (IAM).

When working with AWS Organizations, customers have the option for central identity management for the entire AWS Organization using AWS IAM Identity Center – a single-sign-on (SSO) and federated identity management service (working with Microsoft Entra ID, Google Workspace, and more).

Since there might be a failure with a remote identity provider (IdP) or with AWS IAM Identity Center, AWS recommends creating two IAM users on the root of the AWS Organizations tree, and an IAM break-glass role on each of the accounts in the organization, to allow access in case of emergency.

The break-glass IAM accounts need to have console access, as explained in the documentation.

Authentication Management

When creating IAM accounts, enforce the use of a strong password policy, as explained in the documentation.

Passwords for the break-glass IAM accounts must be stored in a secured vault, and once the work on the break-glass accounts is over, the passwords must be replaced immediately to avoid reuse.

AWS recommends enforcing the use of MFA for any privileged access, as explained in the documentation.

Access Management

Access to resources inside AWS is managed using AWS IAM Roles.

AWS recommends creating a break-glass IAM role, as explained in the documentation.

Access using break-glass IAM accounts must be temporary, as explained in the documentation.

Auditing

All API calls within the AWS environment are logged into AWS CloudTrail by default, and stored for 90 days.

As best practices, it is recommended to send all CloudTrail logs to a central S3 bucket, from the entire AWS Organization, as explained in the documentation.

Since audit trail logs contain sensitive information, it is recommended to encrypt all data at rest using customer-managed encryption keys (as explained in the documentation) and limit access to the log files to the SOC team for investigation purposes.

Audit logs stored inside AWS CloudTrail can be investigated using Amazon GuardDuty, as explained in the documentation.

Resource Access

To allow secured access to EC2 instances, AWS recommends using EC2 Instance Connect or AWS Systems Manager Session Manager.

To allow secured access to Amazon EKS nodes, AWS recommends using AWS Systems Manager Agent (SSM Agent).

To allow secured access to Amazon ECS container instances, AWS recommends using AWS Systems Manager, and for debugging purposes, AWS recommends using Amazon ECS Exec.

To allow secured access to Amazon RDS, AWS recommends using AWS Systems Manager Session Manager.

Handling break-glass scenarios in Azure

Below is a list of best practices provided by Microsoft for handling break-glass scenarios:

Identity Management

Although Identities in Azure are managed using Microsoft Entra ID (formally Azure AD), Microsoft recommends creating two cloud-only accounts that use the *.onmicrosoft.com domain, to allow access in case of emergency and case of problems log-in using federated identities from the on-premise Active Directory, as explained in the documentation.

Authentication Management

Microsoft recommends enabling password-less login for the break-glass accounts using a FIDO2 security key, as explained in the documentation.

Microsoft does not recommend enforcing the use of MFA for emergency or break-glass accounts to prevent tenant-wide account lockout and exclude the break-glass accounts from Conditional Access policies, as explained in the documentation.

Access Management

Microsoft allows customers to manage privileged access to resources using Microsoft Entra Privileged Identity Management (PIM) and recommends assigning the break-glass accounts permanent access to the Global Administrator role, as explained in the documentation.

Microsoft Entra PIM allows to control of requests for privileged access, as explained in the documentation.

Auditing

Activity logs within the Azure environment are logged into Azure Monitor by default, and stored for 90 days.

As best practices, it is recommended to enable diagnostic settings for all audits and “allLogs” and send the logs to a central Log Analytics workspace, from the entire Azure tenant, as explained in the documentation.

Since audit trail logs contain sensitive information, it is recommended to encrypt all data at rest using customer-managed encryption keys (as explained in the documentation) and limit access to the log files to the SOC team for investigation purposes.

Audit logs stored inside a Log Analytics workspace can be queried for further investigation using Microsoft Sentinel, as explained in the documentation.

Microsoft recommends creating an alert when break-glass accounts perform sign-in attempts, as explained in the documentation.

Resource Access

To allow secured access to virtual machines (using SSH or RDP), Microsoft recommends using Azure Bastion.

To allow secured access to the Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS) API server, Microsoft recommends using Azure Bastion, as explained in the documentation.

To allow secured access to Azure SQL, Microsoft recommends creating an Azure Private Endpoint and connecting to the Azure SQL using Azure Bastion, as explained in the documentation.

Another alternative to allow secured access to resources in private networks is to use Microsoft Entra Private Access, as explained in the documentation.

Handling break-glass scenarios in Google Cloud

Below is a list of best practices provided by Google for handling break-glass scenarios:

Identity and Access Management

Identities in GCP are managed using Google Workspace or using Google Cloud Identity.

Access to resources inside GCP is managed using IAM Roles.

Google recommends creating a dedicated Google group for the break-glass IAM role, and configuring temporary access to this Google group as explained in the documentation.

The temporary access is done using IAM conditions, and it allows customers to implement Just-in-Time access, as explained in the documentation.

For break-glass access, add dedicated Google identities to the mentioned Google group, to gain temporary access to resources.

Authentication Management

Google recommends enforcing the use of MFA for any privileged access, as explained in the documentation.

Auditing

Admin Activity logs (configuration changes) within the GCP environment are logged into Google Cloud Audit logs by default, and stored for 90 days.

It is recommended to manually enable data access audit logs to get more insights about break-glass account activity, as explained in the documentation.

As best practices, it is recommended to send all Cloud Audit logs to a central Google Cloud Storage bucket, from the entire GCP Organization, as explained in the documentation.

Since audit trail logs contain sensitive information, it is recommended to encrypt all data at rest using customer-managed encryption keys (as explained in the documentation) and limit access to the log files to the SOC team for investigation purposes.

Audit logs stored inside Google Cloud Audit Logs can be sent to the Google Security Command Center for further investigation, as explained in the documentation.

Resource Access

To allow secured access to Google Compute Engine instances, Google recommends using an Identity-Aware Proxy, as explained in the documentation.